INTRODUCTION

On March 6, 2025, Malaysia’s Parliament fast-tracked and passed the Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) Bill after its third reading. The goal is to regulate carbon capture and storage activities in Peninsular Malaysia and Labuan, while hoping to rake in major investments and boost economic growth.

It sounds like a climate win. The bill promises to curb carbon emissions and tackle climate change head-on. But beneath the surface, it could be little more than layer of greenwashing with little real impact. In other words, a bill that looks eco-friendly but doesn’t walk the talk.

The CCUS Bill opens the door for the construction and operation of carbon capture and storage (CCUS) facilities across Peninsular Malaysia, allowing CO₂ to be trapped and stored underground. The government is banking big on this, expecting the industry to pull in over USD 200 billion in investments over the next 30 years and create 200,000 jobs by 2050.

But not everyone’s buying the hype. Environmental groups like the Gabungan Darurat Iklim Malaysia (GDIMY) are waving red flags. The bill was rushed through Parliament with minimal public consultation.

There’s also growing unease that Malaysia could end up as the world’s carbon dumping ground. BAKO (the Environmental, Climate Crisis & Indigenous Peoples Bureau) of the Socialist Party of Malaysia (PSM) has called for the bill to be re-examined and debated more thoroughly in Parliament before being rushed into law. Malaysia might just become a convenient backyard for wealthy nations to bury their carbon mess.

CCUS BILL DOESN’T APPLY IN SABAH AND SARAWAK: STATES ASSERT CARBON AUTONOMY

The CCUS Bill only covers Peninsular Malaysia and the Federal Territory of Labuan, excluding Sabah and Sarawak entirely. That omission has sparked questions about how these two East Malaysian states plan to chart their own course when it comes to carbon capture and storage.

Both Sabah and Sarawak are standing firm on their constitutional rights: land and forestry matters fall strictly under state jurisdiction.

Sabah’s Deputy Chief Minister, Jeffrey Kitingan; federal CCUS laws don’t apply in Sabah. The state intends to manage its own carbon capture sector, with full control over land and resource decisions. Whether Sabah will welcome or reject future CCUS facility proposals remains to be seen.

Sarawak has enacted its own Land (Carbon Storage) Regulations 2022 to govern carbon storage activities within its borders. According to Dr Hazland Abang Hipni, the state’s Deputy Minister for Energy and Environmental Sustainability, no carbon storage site can be developed without the state government’s green light. However, we do worry the Sarawak’s regulations may be riddled with loopholes, potentially offering inadequate environmental safeguards and leaving the door open to unchecked exploitation of natural resources. There’s also concern that Sarawak’s framework might fall short of aligning with international standards for carbon management and long-term storage.

Sarawak’s Deputy Minister for Energy and Environmental Sustainability, Dr Hazland Abang Hipni. Image source: https://www.theborneopost.com/2024/05/23/putrajayas-proposed-ccus-bill-not-applicable-in-sarawak-says-dr-hazland

MALAYSIA’S CCUS IN ACTION: KASAWARI AND LANG LEBAH PROJECTS

Malaysia has already jumped into the CCUS bandwagon with two major projects off the coast of Sarawak: Kasawari and Lang Lebah.

The Kasawari Project, located about 200 km offshore from Bintulu in the Kasawari gas field, marks a national first. Operated by Petroliam Nasional Berhad (Petronas), this facility is Malaysia’s pioneering CCUS development. Backed by a hefty investment of around RM4.5 billion, the project aims to capture up to 3.3 million tonnes of CO₂ annually making it one of the largest CCUS initiatives in the region.

The first gas production from Kasawari was slated to begin in 2023.

The Lang Lebah Project is based in the gas field within Block SK410B, near the waters of Sarawak. Initially spearheaded by Thailand’s PTTEP in collaboration with Petronas. It was projected to kick off operations in 2027, with an ambitious production capacity of up to one billion cubic feet of gas per day. However, in February 2025, PTTEP pulled the plug on several major tenders, throwing the project’s future into uncertainty.1

WHAT IS CARBON?

Carbon, symbolised as C, is a fundamental chemical element found in all living things. It exists in various forms, from coal and graphite to the dazzling brilliance of diamond.

Beyond its natural forms, carbon is a major player in the world’s energy system. It’s a core ingredient in fossil fuels like coal, petroleum, and natural gas; fuels that power industries, transport, and homes globally. When combined with oxygen, carbon forms carbon dioxide (CO₂), a compound vital for plant photosynthesis but also a major greenhouse gas influencing Earth’s climate.

WHY TOO MUCH CARBON IS A PROBLEM?

Carbon especially in the form of carbon dioxide (CO₂) is a natural and essential part of Earth’s ecosystem. In fact, about 18% of the human body is made up of carbon. But when there’s too much CO₂ in the atmosphere, it triggers serious environmental consequences.

Since the dawn of the Industrial Era around 1750, atmospheric CO₂ levels have skyrocketed. Back then, it hovered around 280 parts per million (ppm). Fast forward to 2024, and that number has soared past 420 ppm, a spike of over 50%. The rate of increase is 100 times faster than the natural rise that occurred at the end of the last Ice Age. Too much carbon in the air means more heat trapped on Earth, setting the stage for a climate crisis.

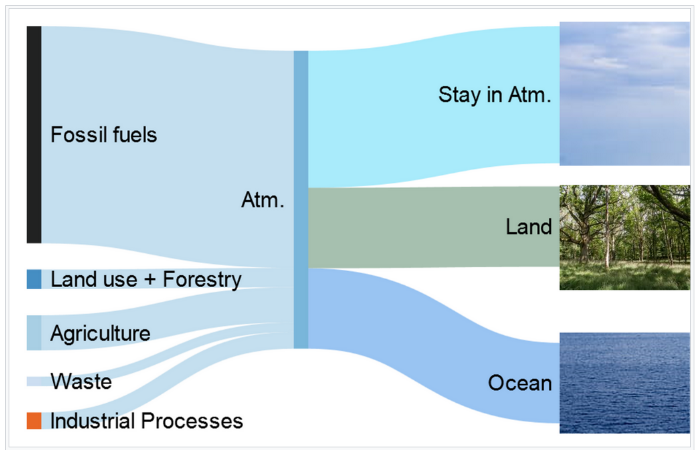

The Industrial Revolution marked the beginning of an era where carbon emissions went into overdrive. The massive use of fossil fuels; coal, oil, and natural gas in industries, transport, and power generation flooded the atmosphere with CO₂.

But that wasn’t all. Deforestation and land-use changes added fuel to the fire. Cutting down forests slashed the Earth’s natural ability to absorb carbon, while decaying organic matter released even more greenhouse gases into the air.

The carbon flow diagram shows us how carbon is both released and absorbed across different natural and systems. Image source: https://energyeducation.ca/encyclopedia/Carbon_flux

Excess CO₂ in the atmosphere supercharges the greenhouse effect, leading to global warming and a cascade of climate disruptions. Here’s what that looks like:

- Rising global temperatures trigger more frequent and intense heatwaves.

- Shifts in rainfall patterns cause floods in some regions, droughts in others.

- Melting polar ice drives up sea levels, threatening low-lying coastal and island communities.

- Ecosystems are thrown off balance, endangering wildlife and biodiversity.

Nature has its own carbon capture system; photosynthesis, where plants absorb CO₂. That’s why protecting and restoring forests is critical. But tree planting alone won’t cut it. For instance, turning carbon-rich peat forests into palm oil plantations releases massive amounts of stored CO₂. And while planting trees sounds like a solution, saplings take time to mature, far too slow to offset the rapid pace of human-driven emissions. In short, we’re emitting CO₂ faster than nature or even forests can soak it up.

Malaysia contributes around 0.72% of global CO₂ emissions, ranking it as the 23rd largest emitter worldwide. While that might seem like a drop in the carbon bucket, it still matters a lot. In the fight against climate change, every percentage point counts. If Malaysia can significantly cut its emissions especially in collaboration with other developing nations within ASEAN, it could spark a regional momentum and apply much-needed pressure on developed countries to follow suit. Malaysia’s carbon policies should embrace the spirit of internationalism: shared responsibility, regional cooperation, and global solidarity.

FOREIGN INVESTMENT OVER A LIVABLE COUNTRY?

The CCUS Bill has triggered alarm bells among environmental activists and affected communities. BAKO’s concern goes deeper than just the effectiveness of the tech, BAKO is questioning the true motives behind it.

While CCUS is often hailed as the poster child of modern climate solutions, the reality is far more complicated. It’s a costly technology, and many pilot projects around the world have fallen short of their promised efficiency. The existence of CCUS is increasingly being used as an opportunity for fossil fuel companies to continue pollute. The narrative goes: “Don’t worry, we can keep burning coal and gas, we’ll just capture the emissions later.”

It’s the illusion of a silver bullet, when what we really need is a serious rethink of the system. Let’s get one thing straight: capturing carbon after it’s been released doesn’t solve the root problem, which is the carbon emissions in the first place. Isn’t it far more logical and sustainable, to cut emissions at the source, rather than rely on costly post-release technology as a band-aid?

Despite that, the buzz around CCUS remains strong. During a recent parliamentary debate, it was revealed that the global CCUS industry is projected to attract a USD 1 trillion (around RM 4.7 trillion) in investment over the next 25 years! Minister of Economy, Rafizi Ramli, has urged the country to “seize the opportunity” and claim its slice of this mega-investment pie. But the real question is: At what cost?

How much of that trillion-dollar promise will actually benefit everyday Malaysians? Will it create quality, long-term jobs, or just a wave of short-term contracts with minimal benefit for local communities? Is this truly an opportunity… or a cleverly disguised trap?

The irony cuts deep. Many Pakatan Harapan leaders now backing the CCUS Bill were once staunch opponents of mega-projects with questionable environmental records. They famously rallied against:

- Lynas Advanced Materials Plant in Kuantan (radioactive waste concerns)

- Forest City in Johor (foreign land ownership and ecological disruption)

- Raub Australian Gold Mining in Pahang (heavy metal pollution)

- Encroachment of Indigenous Ancestral Lands in Peninsular Malaysia (land grabs and deforestation)

Back then, their battle cry was “People and the Environment First.” So now the question hangs in the air: What changed?

During his tenure under the Pakatan Harapan administration (2019–2021), Dr. Mahathir Mohamad publicly declared that he never supported the controversial Forest City project in Johor, citing concerns over its environmental impact and foreign ownership issues. Image source: https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2022/01/06/i-never-endorsed-forest-city-says-dr-m/

THE UNANSWERED QUESTIONS FROM RAFIZI

When the CCUS Bill was hurriedly passed in the Dewan Rakyat on March 6, 2025, it left behind a trail of unanswered questions, critical ones. Even during the Dewan Negara session on March 25, the Senators raised sharp, important queries that deserved more than just surface-level replies.

A memorandum submitted to the Dewan Negara on March 19, 2025, by GDIMY, played a role in shaping that debate. It empowered 17 Senators to dig deeper and press the government for accountability. Still, the silence on some of the most pressing issues speaks volumes. What exactly are we walking into and who truly benefits?

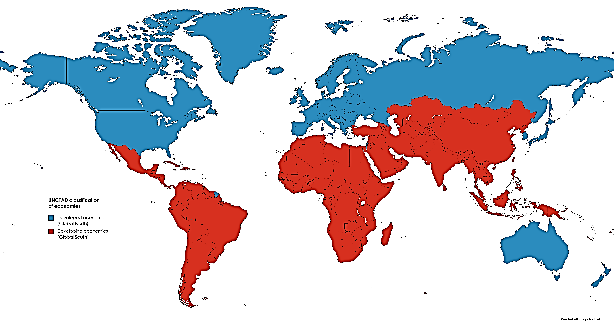

- If CCUS is so promising, why aren’t developed nations like Japan, Singapore, or those in Europe building large-scale CCUS projects on their own turf? Instead, countries like Japan are outsourcing their emissions, shipping their carbon to be stored in developing nations like Malaysia. If this technology creates so many jobs and benefits, why aren’t they keeping it at home?

- Will the CCUS Bill turn Malaysia into a dumping ground for carbon from wealthy, high-polluting nations? In other words, are we about to become a carbon sewer for the industrialized world, cleaning up their mess while they continue business as usual?

- Historically, countries in the Global South, including Malaysia, have long been exploited by the Global North, much of which consists of former colonial powers. The construction of large-scale CCUS facilities in the Global South threatens to reinforce this old imbalance, turning developing nations into storage sites for carbon emitted elsewhere. Are we witnessing a new form of climate colonialism?

A stark visual divide shows the Global North (in blue) and Global South (in red), a reminder of a world still shaped by colonial histories and economic inequality. Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_North_and_Global_South

- Is foreign investment, even through unproven technology, a higher priority for Rafizi Ramli and the MADANI Government than protecting the environment or securing sustainable outcomes?

- Why hasn’t the government chosen to kickstart Malaysia’s green economy with renewable energy instead? The billions earmarked for CCUS could be redirected toward building and operating solar, wind, or hydro facilities, solutions that are already proven to reduce emissions. Yes, the upfront costs are high, and grid integration poses challenges, but wouldn’t that be a smarter long-term investment than banking on post-emission carbon traps?

- Is Malaysia’s push for CCUS turning into a race to the bottom with ASEAN neighbours like Indonesia and the Philippines? It’s worth asking why to compete in carbon storage when we could lead the region in renewable energy collaboration instead? Malaysia is already one of the world’s top producers of photovoltaic cells, while Indonesia and the Philippines boast massive geothermal potential. So why aren’t we pooling our strengths to drive a cleaner, homegrown energy future for Southeast Asia?

- Then there’s the claim, often repeated by Rafizi Ramli, that civil society groups think tree planting is the magic fix for carbon emissions. Let’s set the record straight: We never said that. As opponents of the CCUS Bill, we’ve always emphasized a holistic approach, one that tackles emissions at the source. Tree planting is part of the solution, yes; but it’s not the solution. Real progress starts with cutting carbon where it begins.

A memorandum was submitted to 58 Senators in the Dewan Negara, by GDIMY, containing insights and recommendations from 19 different groups, including BAKO. It served as a collective call for deeper scrutiny, transparency, and accountability on the CCUS Bill. For further reading: – https://sosialis.net/2025/03/19/jangan-tergesa-gesa-luluskan-ruu-ccus/

WHY WE OPPOSE THE CCUS BILL?

Rafizi Ramli has repeatedly claimed that CCUS projects won’t use Malaysian government funds. While that’s not my main concern right now, it’s worth revisiting shortly. The bigger issue is Malaysia’s direction. Because let’s be honest, doesn’t CCUS give fossil fuel companies a free pass to keep polluting under the guise of business-as-usual?

CCUS is often designed with ideal conditions in mind, but reality paints a different picture. These projects are prone to maintenance challenges, operational hiccups, and feedstock variability, making them far less reliable than promised.

The Global CCS Institute, an Australia-based organization that actively promotes CCUS development worldwide, often claims that carbon capture rates can hit 90% or higher. But those numbers are typically drawn from highly controlled, best-case scenarios, like the Sleipner project in Norway. There, nearly 1 million tonnes of CO₂ are captured annually, with offshore gas processing achieving around 90% efficiency.

CCUS at Sleipner, Norway, often cited as a gold standard for carbon capture, has reportedly achieved up to 90% CO₂ capture efficiency from offshore gas processing. Image source: https://www.equinor.com/news/archive/2019-06-12-sleipner-co2-storage-data

Why was Sleipner so successful? It’s a medium-scale project, relatively easy to monitor and control, with ideal underground geology for CO₂ storage. On top of that, Norway’s carbon tax policies gave investors extra motivation to make it work.

But zoom out, and the picture gets much murkier. A 2020 study by MIT found that most CCUS projects, especially in the power generation sector, achieved far lower carbon capture rates due to technical and economic barriers. By 2022, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) reported that the average global CO₂ capture rate for operational CCUS projects was just 49%. Projects like Petra Nova (Texas), Gorgon (Australia), and Kemper County (Mississippi) all underperformed, falling far short of their environmental promises.

One major reason CCUS performance often falls short of expectations is the massive technical challenges. Scaling up CCUS varies widely across industries, and in non-gas sectors, the carbon capture rate tends to be much lower. What’s more, 20–30% of a project’s energy output is often consumed just to capture the CO₂; dramatically reducing overall system efficiency.

Then there’s the cost. High operational expenses make many projects economically fragile. When oil or gas prices dip, CCUS facilities like Petra Nova become financially unsustainable, leading to shutdowns or scaled-back operations.

RAFIZI’S DEWAN NEGARA SPEECH: FACTS THAT DESERVE A SECOND LOOK

During his closing remarks on the CCUS Bill in the Dewan Negara, Economic Minister Rafizi Ramli cited several claims.

His reference to Japan’s Tomakomai CCS Project as having “long-term data.” But here’s the truth: the Tomakomai project only began in 2016, and crucially, it hasn’t yet faced a major earthquake. While Japan is known for its world-class engineering standards, the risk of CO₂ leakage during a powerful seismic event remains unpredictable.

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, which caused unexpected geological shifts, is a sobering reminder that subsurface behaviour can’t be fully controlled, no matter how advanced the design. In the context of CCUS, that uncertainty carries weighty environmental stakes.

Japan’s Tomakomai project may sound impressive, but Malaysia isn’t Japan, and geology matters. Our seismic profile is different, and so is our climate. Applying Japan’s CCUS model here without location-specific risk assessments is not just careless, it’s dangerous. Malaysia’s tropical climate and monsoon floods introduce a whole new set of challenges. Flooding can destabilize CO₂ storage sites and damage pipelines, raising serious concerns about long-term containment.

On top of that, CCUS demands constant monitoring and high-intensity maintenance. For developing countries like Malaysia, where disaster management capacity is limited, this poses a real risk.

Take the tragic case of Lake Nyos in Cameroon, where a sudden release of CO₂ killed 1,746 people and over 3,500 livestock. Although unrelated to CCUS, it’s a chilling reminder of what can happen when large volumes of carbon escape into the environment.

While the Lake Nyos disaster in Cameroon wasn’t caused by CCUS, it remains a crucial case study because it involved the sudden release of a massive amount of carbon dioxide into the environment—with devastating consequences. Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Nyos_disaster

If you’d like to dig deeper into the real-world challenges of CCUS around the globe, here are some notable projects worth researching, each with its own lessons, limitations, and controversies. These cases highlight the technical, environmental, and economic risks tied to carbon capture and why we need transparent, science-driven policy before scaling it up.

Suresh Kumar

Central Commitee

Parti Sosialis Malaysia