by Rani Rasiah

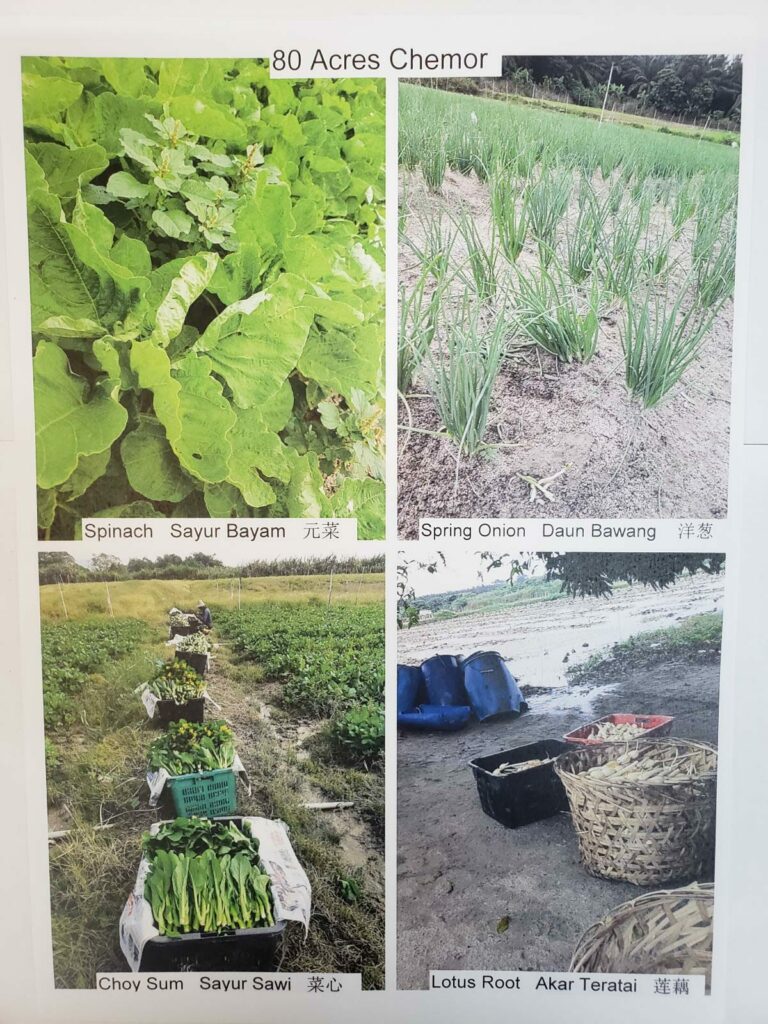

The destruction of another 30 acres of thriving farmland in the Kanthan food farming belt was not just a terrible loss to the 6 farmers tilling the land. Malaysians, particularly Perakians have lost 30 acres of farmland that has been traditionally supplying the Menglembu wholesale market and elsewhere with spinach (bayam), kangkong, onion leaves, corn and star fruit.

Yet food security seemed to be a trivial consideration for the authorities involved in the forced eviction of the 6 farmers on 24/10/2023. Backed by their Section 425 National Land Code 7-day notice, and disregarding all appeals to the Prime Minister, Perak MB, the Director of Lands and Mines (PTG), and the Perak State Economic Development Corporation (PKNP), the state used its full might to clear the land. They brought in heavy machinery, the Light Strike Force of the police, and enforcers from the land office. PTG officers acting like thugs threatened to drive their vehicles into the human blockade of farmers and PSM activists trying to protect the farms. Brute force was used against two women activists one of whom sustained a dislodged tooth and bleeding nose from a fractured facial bone after falling face first on the ground. Bulldozers ran over irrigation pipes and sprinklers completely wrecking them. Four people, farmers and PSM activists were arrested and dragged to the Black Maria parked nearby. And thereafter the demolishers set to work, slashing vegetables and fields of corn ready for harvesting in 2 weeks.

The Kanthan farming belt is in the PM’s Tambun parliamentary constituency, and it is to his credit that concerned officers from his Service Centre were present from early and were clearly trying their best to negotiate with the PTG and PKNP representatives to stop. But after several rounds of negotiations with the different agencies, they failed to persuade the PTG who remained adamant, saying that he would withdraw only if instructed by the Perak MB, and that not even the PM could stop the demolition. It was an instant lesson on the division between Federal and state powers, land being a state matter. Nevertheless it was unbelievable that the PM himself could not prevail.

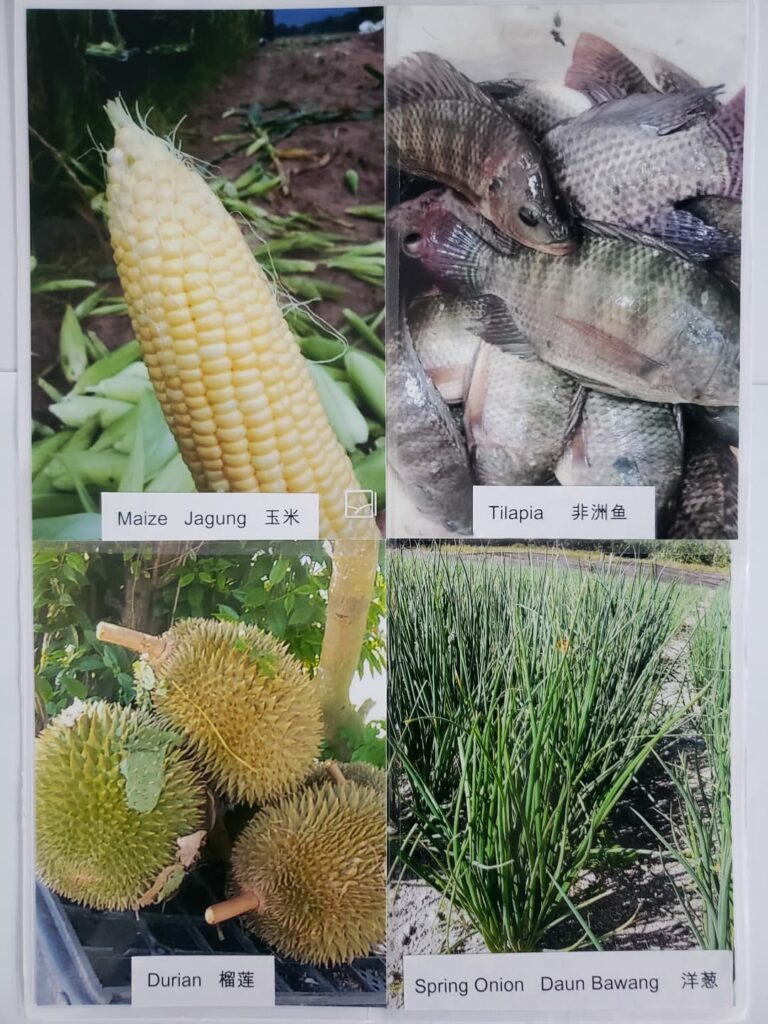

Who are these farmers? According to the government and PKNP, they are trespassers, petani haram, illegally tilling government land. These 6 farmers are among less than 500 farmers on over 2500 acres of land straddling 5 New Villages – Kg Baru Rimba Panjang, Kg Baru Kanthan, Kg Baru Kuala Kuang, Kg Baru Tanah Hitam, and Kg Baru Changkat Kinding – stretching from Sg Siput to Chemor to Tg Rambutan. Farmers in the Kanthan belt alone produce 60 tons of vegetables and fruits a day. The farmers in this area are the largest corn producers in the whole of Malaysia. Yet ironically, they bear the label of trespassers.

The farming community here, hailing from the new villages, is into its third generation, having begun in the 1930s to feed the growing immigrant population in the tin mines, estates and the newly established towns. The early farmers faced the daunting task of growing food, in those days, largely tapioca, on abandoned tin mines. In the decades that followed, they vastly improved the soil and converted the many mining ponds into convenient and reliable water sources for irrigation. The varied and bountiful yield of vegetables and fruits from these grounds are testimony to the sheer hard work, that would have gone into the transformation of the land use from mining to agriculture.

The formulation of the National Land Code in 1965 dispossessed these gritty farmers and turned them into trespassers and squatters, with no rights to the land they had pioneered.

The farmers would continue to work relatively undisturbed for a few more decades applying for leases and temporary occupation licenses (TOL) and engaging with the land office to legalise their status. In the 1990s when land began to be sold for large profits, with kickbacks for all involved, entire farmlands were up for grabs. PKNP began alienating the land to rich corporations and entering into joint ventures.

In recent years the farmlands have been in a permanent state of siege and the farmers have continued to cultivate their crops in the shadow of menacing bulldozers. Either the state sends eviction notices or companies to whom land is alienated take them to court. Where they will lose because the law favours the grant holder over the tiller of many generations.

Food security has become a pressing concern for Malaysians who are now facing food shortages and rising prices of the most basic of needs. Both the Federal and state governments have placed food security high on their agendas. But the Kanthan eviction seriously undermines their credibility. What was seen in Kanthan was the insecurity of food production.

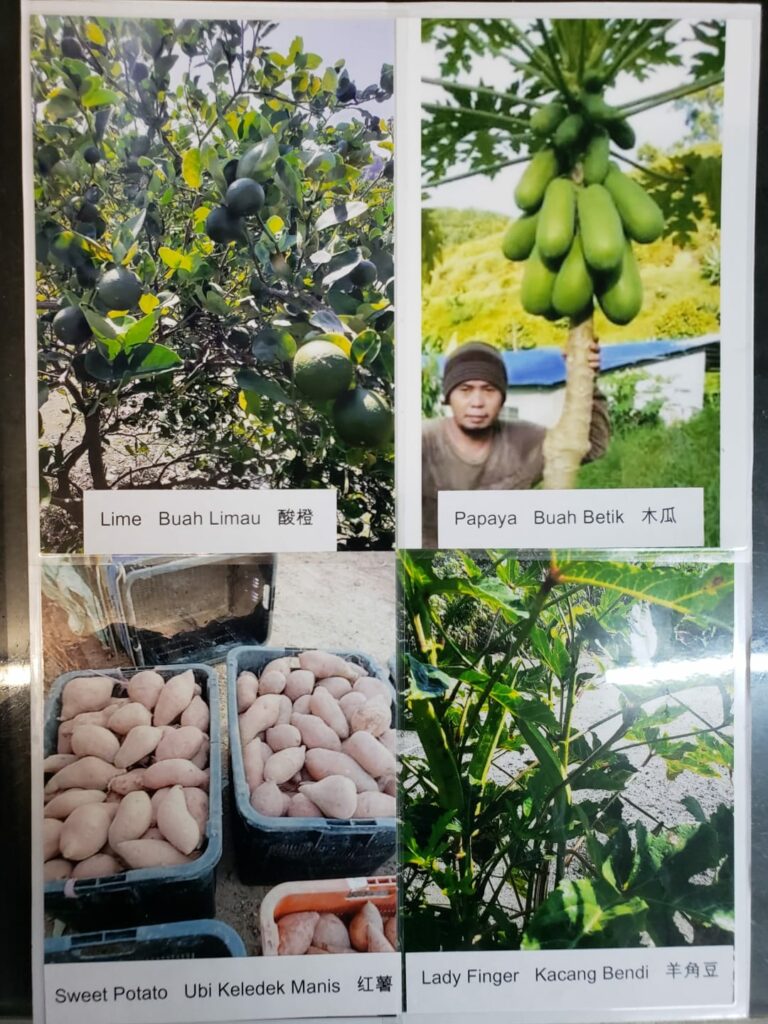

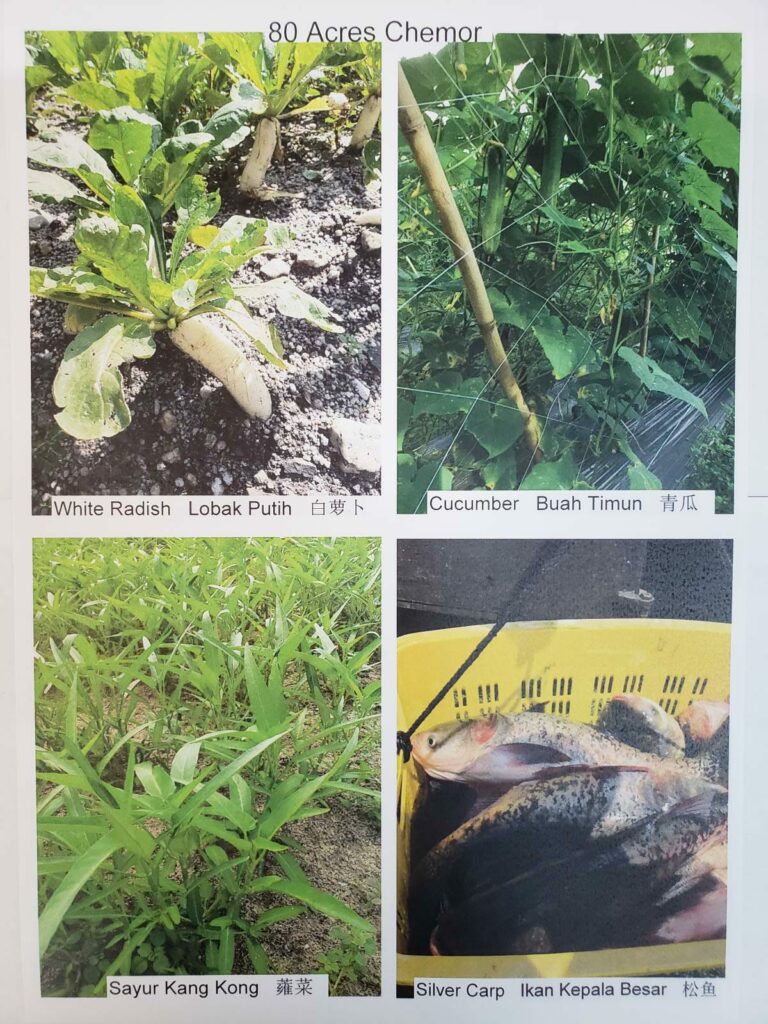

Measures should have been taken to support and encourage the abundant production of vegetables and other food – lotus root, kangkong, spinach, ladies finger, pumpkin, cucumber, chillies, lettuce, groundnuts etc, corn, fish and fruits – in these farming lands. This is an area that should have been and still can be gazetted as a food production area.

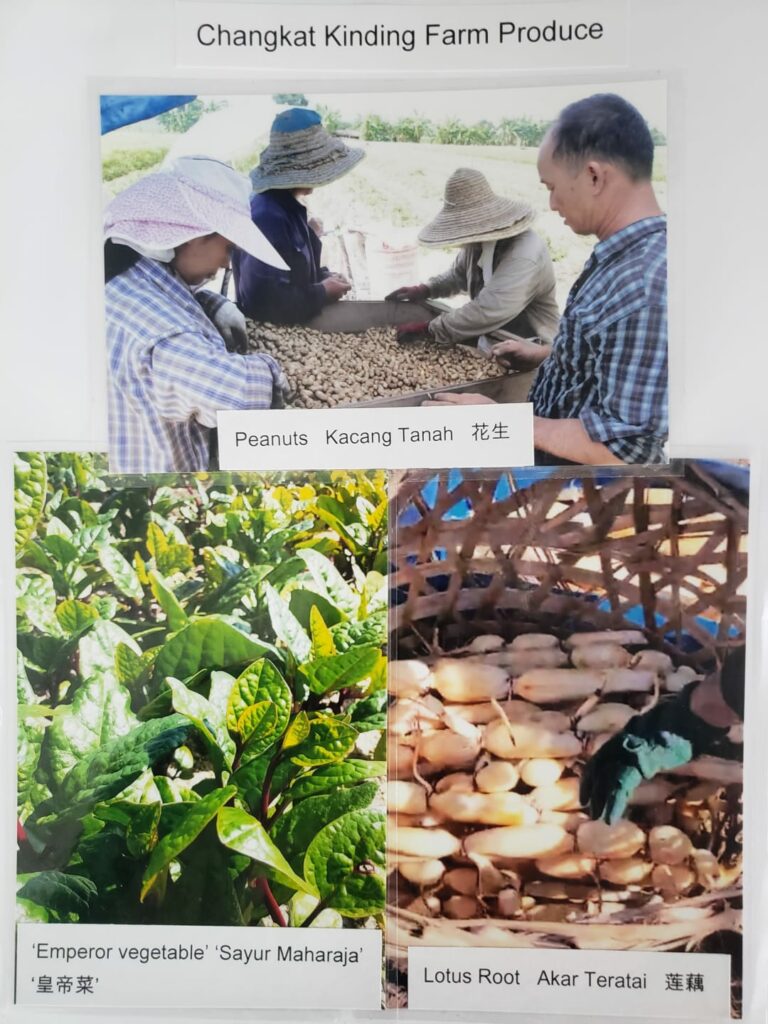

A favourite complaint of the state government is that the farmers have refused to accept their offer of an alternative site in Changkat Kinding. Some of the farmers have indeed been offered alternative land but when they visited the area they found that they were being offered a hill slope, with stony soil, and a pond at the foothill on which economic activity such as fish rearing and cattle farming depend. They were offered 2 acres of land which was in contrast to the average 4 acres they were working on. The attitude of the state reflects a refusal to acknowledge the contribution of the farming community towards food security. They are seen as illegal, free riders, and blocking development.

The cultivation of vegetables, and fruits, the rearing of fish and livestock is an unglamourous occupation. It’s backbreaking work. Spring onions need to be planted one by one, said a farmer waving his hand across a field of the vegetable that’s widely used to garnish food. Most of the farmers are older men and women, and most of the younger generation have moved to other occupations. Naturally as such, the farming community has dwindled to less than half its size. Some farmers have also voluntarily given up rather than fight eviction.

In many countries, farmers are offered subsidies to support and facilitate food production for domestic consumption, at the very least. But here, where initiative and input are from the farmers themselves mostly, farming is a thankless task.

Malaysians should recognize and oppose policies that are harmful to food security instead of allowing our omnipresent racial prejudices from clouding our rationality. In this instance the farmers being displaced are ethnic Chinese. There are instances of Malay farming areas too that are threatened with extinction when no alternative farming land is allocated to replace those that are alienated. Indian cattle rearers too are hounded for grazing their cattle on land that is not theirs. All of them have something in common: they are all landless farmers, and therefore illegal. Even though what all of them produce is halal, sold in our markets and vital for local consumption, it is a tough struggle for all these landless farmers. It makes no sense to dismiss them as illegal. The government should instead change its attitude, and enable these farmers to work on their farms peacefully for the sake of achieving food self-sufficiency.

Gallery of produce from the farmers in the Kanthan belt: